Bayʿah or Bay’a (Arabic: بَيْعَة, “Pledge of Allegiance“), is an oath of allegiance to a leader. It is known to have been practiced by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Bayʿah is sometimes taken under a written pact given on behalf of the subjects by leading members of the tribe with the understanding that as long as the leader abides by certain requirements towards his people, they are to maintain their allegiance to him. Bayʿah is one of the foundations of the Middle Eastern monarchy.

“…in relation to the concept of political succession and accession, bayʿa refers to an agreement of a reciprocal nature between a nominated or appointed leader and the community.” Mehran Tamadonfar, The Islamic Polity and Political Leadership: Fundamentalism, Sectarianism, and Pragmatism (Boulder: Westview Press, Inc.,1989), 91

PRE-ISLAMIC ERA

The concept comes from before the advent of Islam.

“In pre-Islamic Arabia, which lacked the presence of a dominant state, this “pledged covenant under oath” was the principal political institution and ensured a method of protection and collaboration between various tribes.” Professor Andrew Marsham, Professor of Classical Arabic Studies and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge

“…the bayʿa ritual and pledge can be viewed simultaneously as both a religious and political rite of submission and loyalty. The ritual grew out of a pre-Islamic environment which relied heavily on verbal communication in the forms of oral alliances, ritual, poetry, and oaths. The inevitable contributions of Near Eastern and Roman customs to Arabian practices also augmented pre-Islamic political reality.” Professor Andrew Marsham, Professor of Classical Arabic Studies and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge

ISLAMIC GENESIS AND DYNASTIC SUCCESSION

The concept of Bay’a was adopted by Prophet Mohammad as a central ritual in Islam. Important to mention that even though Islam is a spiritual practice, there’s no separation between religion and State. Eventually, it became standard political praxis to all the Arab world since then regardless of religion since some Arab peoples became Christian.

“A companion reports that he came to the Prophet and exchanged Bayʿah to become a Muslim; he then enumerated the pre-Islamic customs which he forsook by his conversion. The Prophet responded, “How successful is the transaction you made!” (mā ghabinat ṣafaqatuka). The word used in this tradition is ṣafaqa, which is a purely commercial term for a transaction and, significantly, also means “handclasp.” Professor Ella Landau-Tasseron, Department of Islam and Middle Eastern Studies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

“In addition to the accounts in the ḥadīth of the use of the bayʿa pledge in establishing and agreeing to the newly dictated tenets of the religion, the Qurʼān itself contains a revelation that also addresses these concerns. Although the word bayaʿa “occurs six times, in four places, in three sura (sūrat Bara’a, or al-Tawba, sūrat al-fath, and sūrat al-Mumtahana, respectively: Q 9:111; Q 48:10, 18; Q 6:12), the Sūrat al-Mumtahaha, or women’s bayʿa, is most closely associated with the pledge of allegiance in secondary sources.” Professor Andrew Marsham, Professor of Classical Arabic Studies and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge

As Professor Andrew Marsham writes in Rituals of Islamic Monarchy:

“Whereas the Qur’ān attests to the use of the verb bāyaʽa in the sense of an oath of allegiance to the leader of the umma taken from those seeking to join it and an oath of loyalty in war taken from existing members of the polity, it makes no mention of the third sense in which it is used in the sources for the first decades of Islam: a pledge taken to recognize a new leader of the umma. However, once the idea of leadership of the polity by one man had been accepted, this third use of the term bāyaʽa was a logical consequence of the first: because a pledge of allegiance expressed obligations owed to an individual, that individual’s death ended the covenant, and his successor required a new pledge.”

The bayʿa should not be viewed as a general election but as the acceptance by the community, or particular people of importance, of a ruler who gained authority through inheritance, usurpation, or nomination. (see S.D. Goitein, Studies in Islamic History and Institutions (Leiden: Brill 1966), 203)

According to Professor Shelomo Dov Goitein (University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University), the bestowal of the Bay’a could even legitimize usurpers, therefore, superseding genealogy and eventual rules of succession.

“The use of ritual symbolism as a means of communication in the transfer of power from one leader to the next cannot be overstated; as David Kertzer writes in Ritual, Politics, and Power, “rituals express the continuity of positions of authority in the fact of the comings and goings of their occupants.” In a sense, bayʿa and other rituals of accession can be viewed as methods of communicating power and authority not just to the individual in question, but to the position, in effect imbuing the “office” itself with a sacrosanct nature.” Bayʿa: Succession, Allegiance, And Rituals of Legitimization in the Islamic World”, Lauren A. Caruso, University of Georgia, 2013, p.32

Dynastic succession became the standard mode of power transfer in 660 C.E. after the end of the first civil war, with the reign of the Sufyanid Umayyads. The then-governor of Syria, Muʿāwiya b. Abī Sufyān (r.661-80), appointed himself caliph and moved the geographical capital of the Islamic empire to Damascus, beginning the Umayyad dynasty (661-750). (see Patricia Crone, God’s Rule: Government and Islam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 33)

The English translation of the Maronite Chronicle relates,

“Many Arabs gathered at Jerusalem and made Muʽāwiya king, and he went up and sat on Golgotha; he prayed there, and went to Gethsemane and went down to the tomb of the blessed Mary to pray in it … In July of the same year (660) the emirs and many Arabs gathered and proffered their right hand to Muʽāwiya. Then an order went out that he should be proclaimed king in all the villages and cities of his dominion, and they should make acclamations and invocations to him.” (see James Douglas Howard-Johnston, emeritus fellow of Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford)

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

The use of the bay’a was also adopted by the Ottoman Empire.

Murphey explains in Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty:

“For a sultan’s role to be fully confirmed, not just swearing of oaths by officials in the divan was required, but also his presence and a visual manifestation among the widest possible group of subjects of all grades and classes. Only some, the viziers and other high-placed court officials, were granted the favour of offering their personal congratulations and subservience in the form of the hand kiss (dest-bus) which required not just visualization, but close approach.” Rhoads Murphy, Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty: Tradition, Image, and Practice in the Ottoman Imperial Household, 1400-1800 (New York: Continuum, 2008), 101-102

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EAST

As a fundamental religious and political practice in the Middle East, the concept has remained current throughout the ages until now.

“The bayʿa has managed to maintain a position of absolute necessity for many governments, and indeed for numerous organizations that exist outside the boundaries of accepted and normative political thought. The use of the bayʿa pledge and ritual are still routinely employed by Middle Eastern governments in the pursuit of legitimacy and public support.” .” Bayʿa: Succession, Allegiance, And Rituals of Legitimization in the Islamic World”, Lauren A. Caruso, University of Georgia, 2013, p.44

“The bayʿa became representative of what Rousseau coined as “civil religion” and for all the varied political groups using the bayʿa ritual the intent is clear; by marrying a ritual grounded in Islamic sacred history with contemporary political ceremonies, political groups, and leaders can fashion a historical narrative which embraces the myth of origin while tending to current needs for legitimacy and stability. The search for legitimacy is constant, and a ritual such as the bayʿa has the backing of established religious and political history, as well as the endorsement of the Prophet Muḥammad himself.” .” Bayʿa: Succession, Allegiance, And Rituals of Legitimization in the Islamic World”, Lauren A. Caruso, University of Georgia, 2013, p.47

With small adaptations, the concept evolved and was a fundamental principle to the legitimization of power in the contemporary countries of the Middle East, both monarchies and republics.

“The particular political and governmental institution embraced by the newly independent countries was diverse, and often, highly contingent on whatever residual colonial presence remained. However, the newly formed governments collectively faced the problem of how to legitimize rule and ensure not only a stable rise to power but also consistently uncontested transfers of sovereignty. The bayʿa was a pivotal step in this process of legitimization and was adapted to fit modern constraints and technologies. As it was used in the past to secure positions of power in the Umayyad and Ottoman Dynasties, the bayʿa was once more employed to assist in the dynastic succession of newly independent countries, such as Syria, Jordan, and Morocco. “ .” Bayʿa: Succession, Allegiance, And Rituals of Legitimization in the Islamic World”, Lauren A. Caruso, University of Georgia, 2013, p.47-48

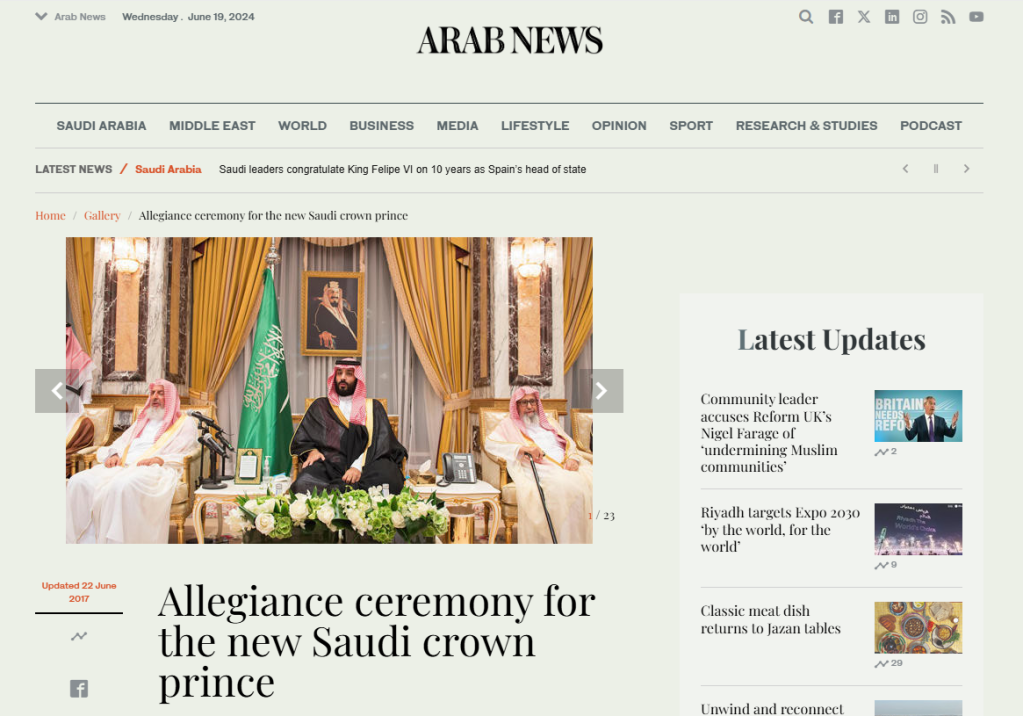

Maybe the more evident use of the concept happens in Saudi Arabia due to the vast number of princes competing for succession.

“In order to combat the high number of challenges coming from various branches of feuding families, ‘Abdul Aziz (Al Saud) embraced the already established mechanism of the bay’a to guarantee backing for his own chosen heir apparent.” J.E. Peterson, “The Nature of Succession in the Gulf,” Middle East Journal 55, no. 4 (2001)

“This was the first in a long line of successive hereditary bayʿāt within the al-Saud family, although the chosen heir was not always the first-born son of the previous ruler. This ambiguous mode of succession was actually written into “the Kingdom’s rough equivalent of a constitution,” with the enactment of the Basic Law in 1992, dictating that future kings of the country must not only be the eldest, but also the most fit to rule.111 Article 5 section b of the Saudi Basic law states:

‘Governance shall be limited to the sons of the Founder King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn ‘Abd ar-Rahman al-Faysal Al Sa’ud, and the sons of his sons. Allegiance shall be pledged to the most suitable amongst them to reign on the basis of the Book of God Most High and the Sunnah of His Messenger (PBUH).’ Basic Law of Governance,” Umm al-Qura Royal Order No. 3397 (1992).” Bayʿa: Succession, Allegiance, And Rituals of Legitimization in the Islamic World”, Lauren A. Caruso, University of Georgia, 2013, p.50

The bayʿa process has been streamlined in Saudi Arabia by the establishment of the Allegiance Committee (al-hayat al-baya), which consists of the sons and grandsons of Abd al-Aziz al-Saud. (see Michael Herb, All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies (Albany: State University of New York, 1999), 36)

Moroccan political culture has also greatly relied on the clout of the bayʿa ritual to justify the rule of the monarchy, and while the bayʿa has played a role in Moroccan dynastic succession rituals since the end of colonial rule, it was more heavily employed during the latter half of Hassan II’s rule (1961-1999) “since the Bayʿa of Layoune in 1979 in Western Sahara, when Sahrawi tribal notables performed this act as a sign of Sahrawi’s attachment to the Moroccan throne.” Although not included in the Moroccan constitution, the bayʿa ritual was mentioned in the Bulletin Officiel in 1979, and “confers divine powers on the King; ‘the holder of the legitimate authority of God’s shadow on earth and his secular arm in the world.’” (see James N. Sater, Morocco: Challenges to Tradition and Modernity (New York: Routledge, 2010), 6-8)

In the Moroccan government, the bayʿa is associated with a dual function; political succession and accession, and also this yearly renewal of allegiance to the king by the political elite and religious scholars or tajdid al wala. (See Abdeslam Maghraoui, “Political Authority in Crisis: Mohammand’s VI’s Morocco,” The Middle East Report 31 (2001)

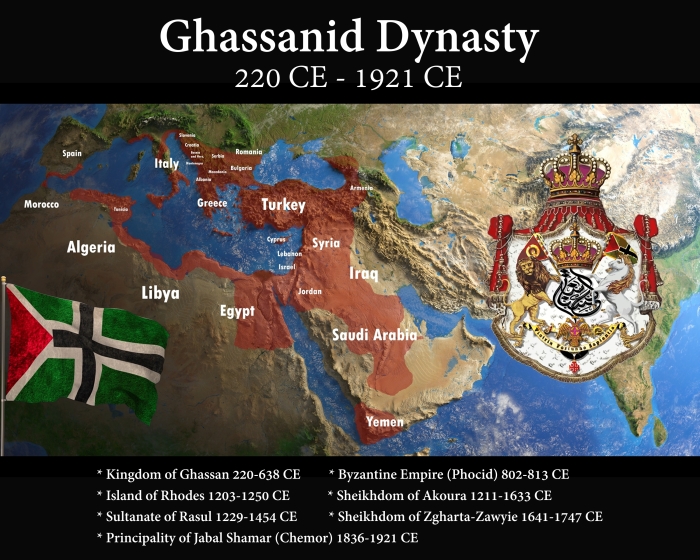

GHASSANID DYNASTY

The Ghassanid Dynasty was (and is) officially Christian, although some Ghassanid princes ruled territories after converting to Islam, like the Rasulid Sultanate (1229-1454 CE) and the Principality of Jabal Shammar (Chemor) (1836-1921 CE). The current internationally recognized heir of the dynasty, HIRH Prince Gharios El Chemor, had his leadership of the Royal House of Ghassan legitimized by the Bay’a from the heads of the El Chemor family in Lebanon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahram, Ariel I. “Iraq and Syria: The Dilemma of Dynasty.” The Middle East Quarterly (2002): 33-42.

“Basic Law of Governance.” Umm al- Qura no. 3397 (1992): 1-13.

Bell, Catherine. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Bengio, Ofra. Saddam’s Word: Political Discourse in Iraq. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bergen, Peter. “Al Qaeda, the Organization: A Five-Year Forecast.” The Annals of the American Academy 618 (2008): 14-30.

Billingsley, Anthony. Political Succession in the Arab World: Constitutions, Family Loyalties and Islam. London: Routledge, 2010.

Bourqia, Rahma. “The Cultural Legacy of Power in Morocco” In In the Shadow of the Sultan: Culture, Power, and Politics in Morocco, 243 -258. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Bravmann, M.M. The Spiritual Background of Early Islam: Studies in Ancient Arab Concepts. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Chejne, Anwar G. Succession to the Rule in Islam: With Special Reference to the EarlyʽAbbasids Period. Lahore: Ashraf Press, 1960.

Chittick, William C. Sufism: A Short Introduction. Oneworld Publications: Oxford, 2000.

Crone, Patricia. God’s Rule: Government and Islam. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Daadaoui, Mohamed. Moroccan Monarchy and Islamist Challenge: Maintaining Makhzen Power. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011.

Ernst, Carl W. Sufism: An essential introduction to the Philosophy and practice of the Mystical Tradition of Islam. Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1997.

Faruqi, Muhammad Yusuf. “Bay’ah as a Politico-Legal Principle: Practices of the Prophet (Peace be on Him) and the Rightly Guided Caliphs and Views of the Early Fuqaha.” Insights 2, no. 1 (2009): 33-56.

Global Muslim Brotherhood Daily Report. “Hamas Leader Pledges Oath to New Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood Leader” Last modified on February 8th, 2010.

Goitein, S.D. Studies in Islamic History and Institutions. Leiden: Brill, 1966.

Gusfield, Joseph R. and Jerzy Michalowicz. “Secular Symbolism: Studies of Ritual, Ceremony and the Symbolic Order in Modern Life” Annual Review of Sociology 10, .1 (1984): 417-435.

Grimes, Ronald. Rite Out of Place: Ritual, Media, and the Arts. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hanne, Eric J. Putting the Caliph in His Place: Power, Authority, and the Late Abbasid Caliphate. New Jersey: Associated University Presses, 2010.

Hawting, Gerald R. The First Dynasty of Islam: the Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Herb, Michael. All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies. Albany: State University of New York: 1999.

Holtman, Phillip. “Virtual Leadership in Radical Islamist Movements: Mechanism, Justifications and Discussion” The Institute for Policy and Strategy (2006).

Howard-Johnston, James. Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East From the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. New York: Longman Inc., 1986.

Kertzer, David. Ritual, Politics, and Power. New York: Vail-Ballou Press, 1988.

Lassner, Jacob and Michael Bonner. Islam in the Middle Ages: The Origins and Shaping of Classical Islamic Civilization. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2010.

Madelung, Wilferd. The Succession to Muḥammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Maghraoui, Abdeslam. “Political Authority in Crisis: Muhammad VI’s Morocco.” Middle East Report 31 (2001).

Malamud, Margaret. “Gender and Spiritual Self-Fashioning: The Master-Disciple Relationship in Classical Sufism.” Journal of American Academy of Religion 64, no. 1 (1996): 89-117.

Marsham, Andrew. Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

Murphy, Rhoads. Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty: Tradition, Image, and Practice in the Ottoman Imperial Household, 1400-1800. New York: Continuum, 2008.

Myerhoff, Barbara. “A Death in Due Time: Construction of Self and Culture in Ritual Drama.” Rite, Drama, Festival, Spectacle: Rehearsals Toward a Theory of Cultural Performance, edited by John J. MacAloon, 149-178. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1984.

Peterson, J.E. “The Nature of Succession in the Gulf.” Middle East Journal 55, no. 4 (2001): 580-601.

Podeh, Elie. “The bayʽa: Modern Political Uses of Islamic Ritual in the Arab World.”

Die Welt des Islams 50 (2010): 117-152. doi:10.1163/157006010X487155

“From Indifference to Obsession: The Role of National State Celebrations in Iraq, 1921-2003.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 37, no. 2 (2010): 179 – 206.

Raposa, Michael L. “Ritual Inquiry: The Pragmatic Logic of Religious Practice.” In Thinking Through Rituals: Philosophical Perspectives, edited by Kevin Schilbrack, 113-127. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Rogan, Hanna. “JIHADISM ONLINE – A Study of How al-Qaida and Radical Islamist Groups Use the Internet for Terrorist Purposes” FORSVARETS FORSKNINGSINSTITUTT (FFI): Norwegian Defence Research Establishment. (2006): 1- 36.

Sater, James N. Morocco: Challenges to Tradition and Modernity. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Schechner, Richard. Performance Theory. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Tamadonfar, Mehran. The Islamic Polity and Political Leadership: Fundamentalism, Sectarianism, and Pragmatism. Boulder: Westview Press, Inc., 1989.

Takim, Liyakat N. The Heirs of the Prophet: Charisma and Religious Authority in Shi’ite Islam. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006.

Trimingham, J. Spencer. The Sufi Order of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Wedeen, Lisa. Ambiguities in Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999.