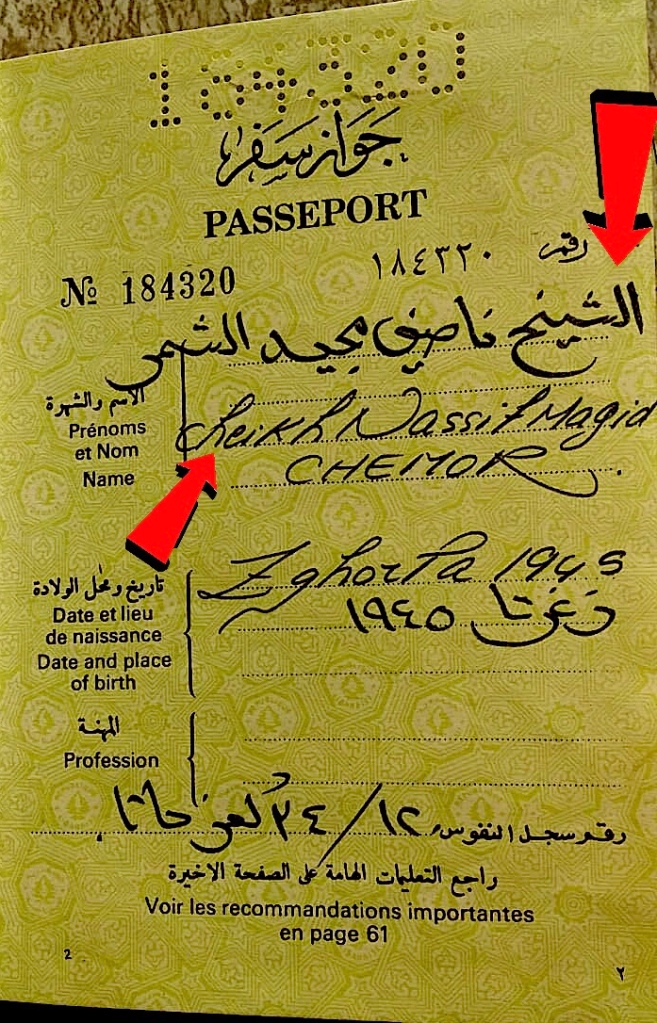

Photo: letter from prophet Mohammad to Ghassanid King Al-Harith VI Abu Chemor * Shamir, also Shamar, Shamour or Chemor is one of the many transliterations of the same Arabic word الشمر

One may argue the reason why the El Chemor Family uses the Royal Ghassanid titles in addition to the “Sheikh” titles. Here are the legal reasons and the historical precedents:

1. The proven legatee succession from the Ghassanid Kings – The mere use of the last name “El Chemor” meant the ones from “Bani Chemor” or “the children of King Chemor” the famous Ghassanid King of the Levant.

“It is a reputed deep-rooted allegation that the heads of Al-Chemor tribe are rooted from Bani Chemor, who are the Christian Kings of Ghassan which belong to Al Jafna.” (Father Ignatios Tannos El-Khoury, Historical Scientific Research: “Sheikh El Chemor Rulers of Al-Aqoura (1211-1633) and Rulers of Al-Zawiye (1641-1747)”Beirut, Lebanon, 1948, p.38)

“This is the history of the Chemor family Sheikhs who are feudal rulers, a genuine progeny of the sons of Ghassan kings of the Levant… one of the most decent, oldest and noblest families in Lebanon.” (ibid p.125)

And the El Chemor family isn’t the only one with these characteristics. There are also two families in Iraq, Oman and UAE that descend directly from the Lakhmid Kings Mundher and Al-Numan:

“The “Mandhari [children of king Mundher] and Na’amani [children of king Al-Numan] tribes” are the main descendants of the Lakhmids in the Persian Gulf. They are, for the most part, the same family with superficial, simple differences. The main difference is that the Na’amani family traces its lineage back to al-Nu’man III ibn al-Mundhir while the Mandhari family traces it back to his grandfather: king al-Mundhir ibn Imr’u al-Qais, but a significant number of members of the Al Mandhari tribe are descendants of king al-Nu’man III ibn al-Mundhir. Both families are mainly situated in the Iraq, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, and the Sultanate of Oman. “

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lakhmids#Al_Mandhari_/_Al_Na’amani_families

In Lebanon, there’s another very important and prestigious family who claim descent from the Lakhmid Kings, the House of Arslan. They have the title of princes just for this link with the Lakhmid dynasty which ended in 602 CE. The Arslan family had a huge role in Lebanese history, especially in the Lebanese independence, however, differently than the El Chemor family, they didn’t rule any territory since the 7th century but still are recognized lawful princes.

* Sworn Legal Statement from the world’s leading Expert in Arab Royal Succession CLICK HERE

* More about the endowment of the Royal titles to the El Chemor family, please CLICK HERE

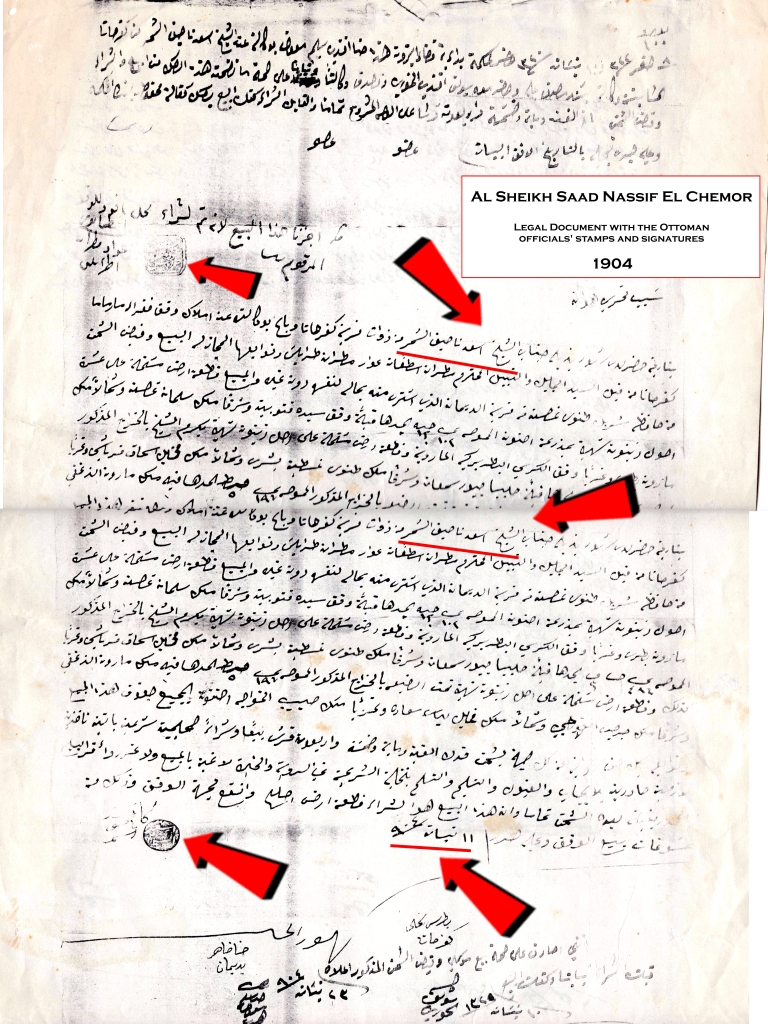

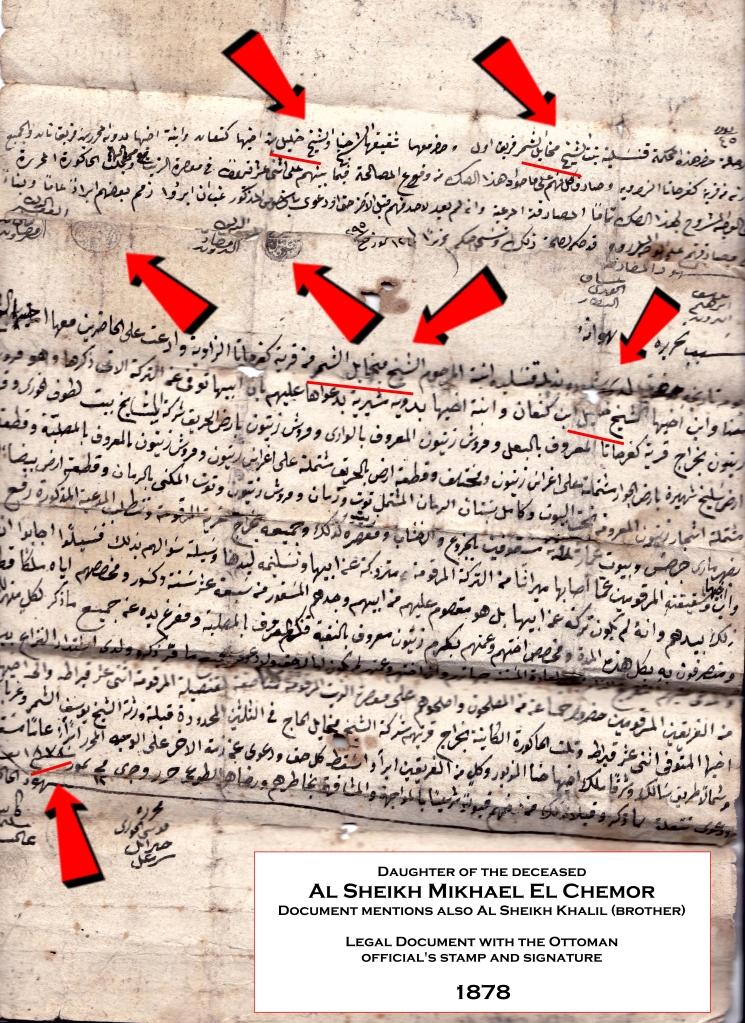

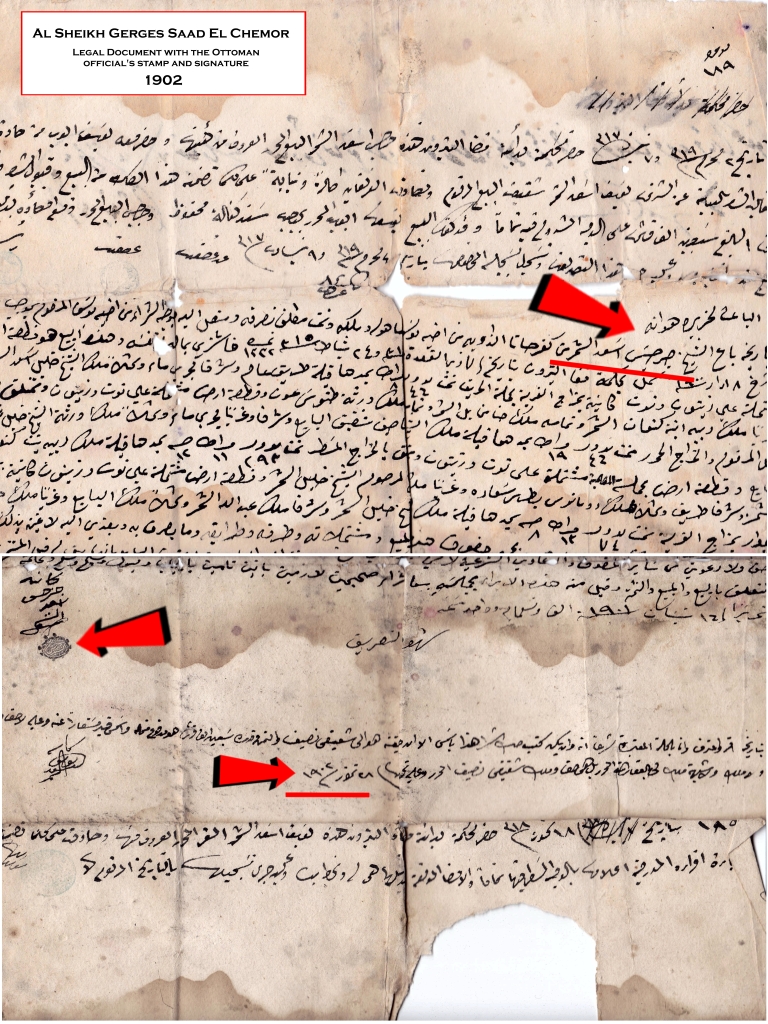

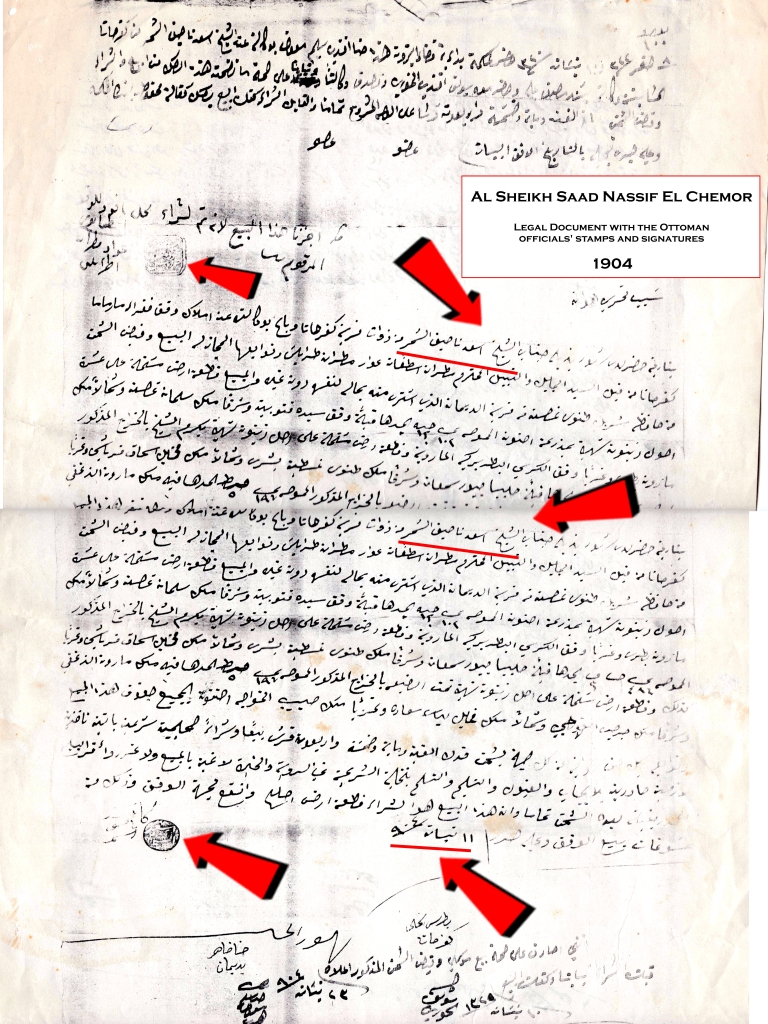

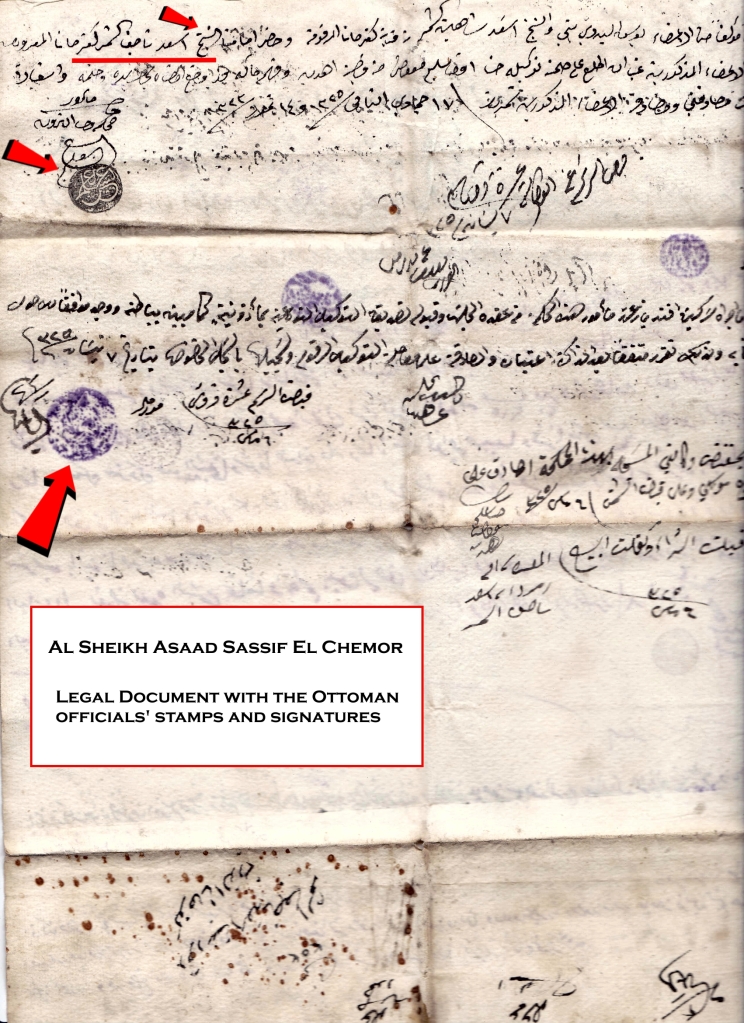

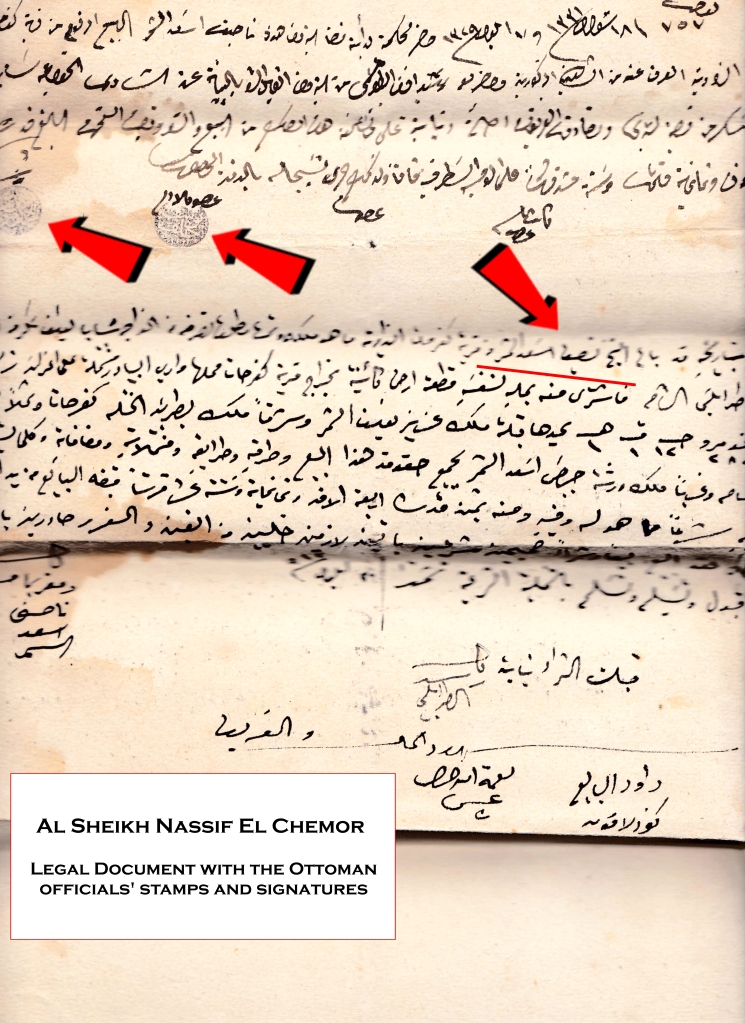

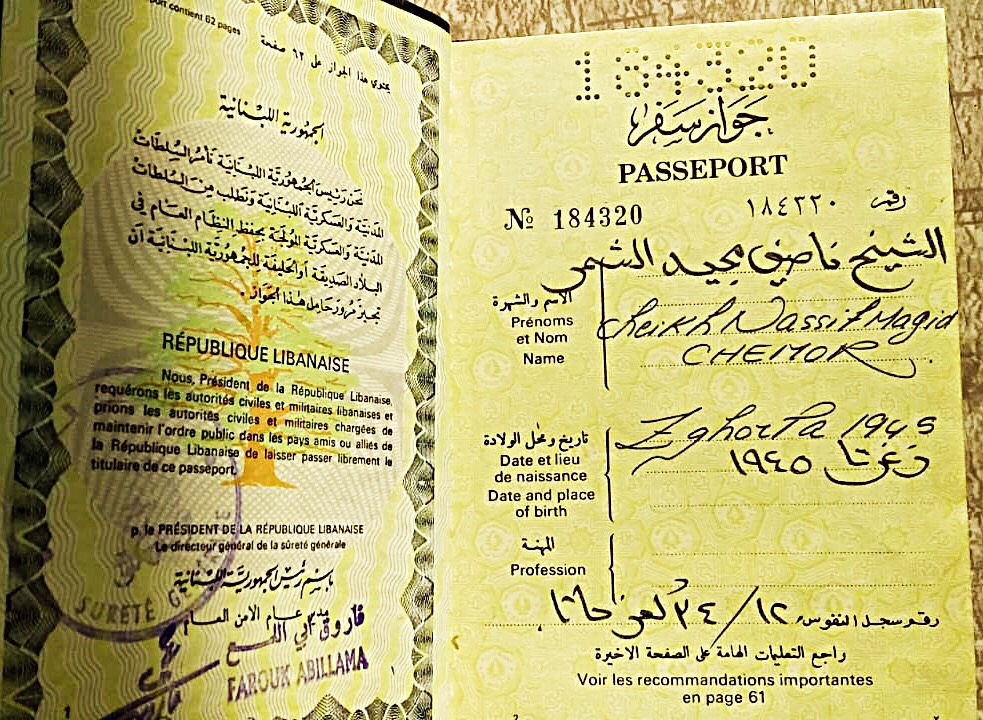

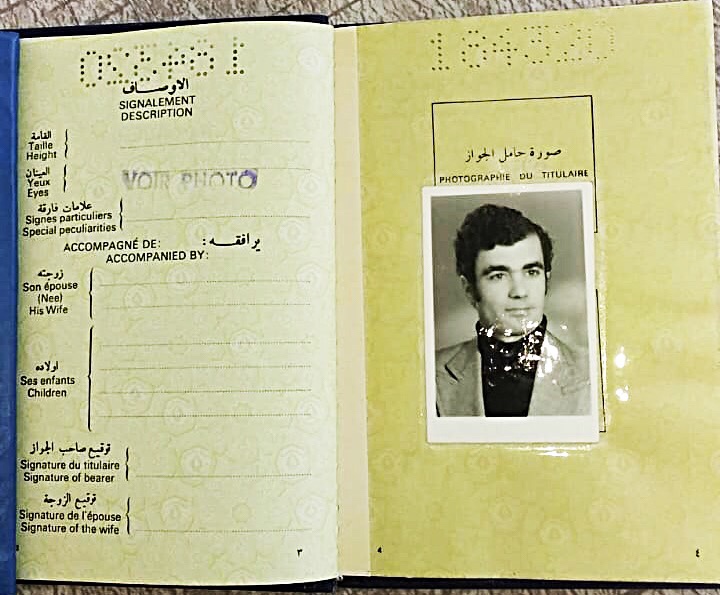

* See historical family documents by CLICKING HERE

2. Arab tradition – a sovereign sheikh is a royal prince by the Arab tradition since pre-Islamic times. The title “sheikh” (in the secular sense) is even more related to hereditary ruler than “Amir” which was originally a military title (coming from the Arabic verb “amr” or “to command”), only associated as being analogous to the western title of “prince” since a few centuries ago. That can be corroborated not only by history but also by the existing Arab States ruled by sheikhs: Kuwait, Bahrain, Bahrain, Qatar, Dubai, Abu-Dhabi, Sharja, etc.

Also important to point that the origin of many of the aforementioned ruling royal families is from Al Azd tribe exactly the same of the El Chemor family, being natural that the traditions are similar, regardless of religion since the Arab laws of succession come mostly from pre-Islamic tribal customs.

The founder of the Ghassanid Dynasty was King Jafna Ibn Amr (ruled 220-265 CE). He was the son of the Azd ruler Amr Ibn Muzaikiya. The other sons of Amr gave origin of other important Arab ruling families like the Al-Said Sultans of Oman, the Al-Nahyam rulers of Abu-Dhabi, the Al-Maktoums rulers of Dubai and the Al-Nasrids rulers of Al-Andaluz (Spain). Originally as part of the Azd tribe, the Sheikhs El Chemor have blood ties with many major Arab ruling houses.

3. Dynastic custom adopting past titles of the family patrimony – it’s perfectly accepted by the European jurisprudence the use of past titles that historically belonged to the family.

For example, Prince Henri, the head of the French Orleans family, uses the title “Count of Paris”, an old title belonging to the family but not used by other ruling head of the family. Count of Paris (French: Comte de Paris) was a title for the local magnate of the district around Paris in Carolingian times. After Hugh Capet was elected King of France in 987, the title merged into the crown and fell into disuse. However, it was later revived by the Orléanist pretenders to the French throne in an attempt to evoke the legacy of Capet and his dynasty.

4. Principle of “de jure” sovereignty – according to this principle, a deposed ruler and his descendants in perpetuity (following the respective laws of succession) keep two of the four powers of sovereignty: “jus majestatis” the right of being respected and recognized by his title and “jus honorum” the right of conferring titles, honors and awards. The two other powers “jus imperium” the right of rule a territory and a people and “jus gladii” the right of command an army and apply the capital penalty, remain dormant until the “de facto” sovereignty is restored. Being a “de jure” sovereign, the decision of the use of titles is a personal prerogative as stated by one of the forefathers of international law, Emmerich de Vattel:

The Law of Nations or the Principles of Natural Law, 1758 CE:

“BOOK 2, CHAPTER 3

Of the Dignity and Equality of Nations: of Titles and Other Marks of Honor

§ 42. Whether a sovereign may assume what title and honors he pleases.

If the conductor of the state is sovereign, he has in his hands the rights and authority of the political society; and consequently he may himself determine what title he will assume, and what honors shall be paid to him, unless these have been already determined by the fundamental laws, or that the limits which have been set to his power manifestly oppose such as he wishes to assume. His subjects are equally obliged to obey him in this as in whatever he commands by virtue of a lawful authority. Thus, the Czar Peter I., grounding his pretensions on the vast extent of his dominions, took upon himself the title of emperor.” https://lonang.com/library/reference/vattel-law-of-nations/vatt-203/

If we accept that a deposed sovereign and his descendants remain being sovereign (just “de jure” or by right, not “de facto” or in fact), the above mentioned by Vattel refers to the power of “jus majestatis”, fully active during the interregnum. Naturally, being the “jus imperii” dormant, in theory, his former “subjects” don’t have an obligation to acknowledge the prince pretender by his title.

“The refugees of Al Ghassani and bani Chemor who seeked refuge to Al ‘Aqoura turned into Maronites because the town now only has Maronites Christians and because Al Chemor tribe are the princes and children of kings, the Maronites reigned them over the land where the document states that: “… and Al ‘Aqoura is their own village from a long time, they can do as they wish…” and Al Chemori family could have taken over the throne due to their relentless efforts, money or battles, no one knows.” (Father Ignatios Tannos El-Khoury, Historical Scientific Research: “Sheikh El Chemor Rulers of Al-Aqoura (1211-1633) and Rulers of Al-Zawiye (1641-1747)”Beirut, Lebanon, 1948, p.42)

The above reference clearly shows sovereignty over the Al-Aqoura region.

The examples in the Middle East are also extensive where many sovereign Sheikhs have decided to use Royal titles like His Majesty King Abdullah I of Jordan who was originally the Emir of Transjordan and his ancestors were Sheriffs of Meca; or His Highness Sheikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, was the 12th Hakim of Bahrain. His son, His Highness Sheikh Isa II bin Salman II Al Khalifa, changed the title to “Emir of Bahrain” in 1971 and his son, His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa has changed the title again in 2002 from Emir (prince) to Malik (king).

According to several encyclopedias, “Amir”, means “lord” or “commander-in-chief”, being derived from the Arabic root ‘a-m-r’ or “command“. Originally, simply meaning “commander-in-chief” or “leader”, usually in reference to a group of people, it came to be used as a title for governors or rulers, usually in smaller states. Therefore, the title had a military – not necessarily royal/noble – connotation.

“The title Emir or Amir was equivalent of that of Commander.” The Black Book of the Admiralty, 1873, V.2, p.xiii (Cambridge University Press, 2012 edition, edited by Travers Twiss)

“In the past, amir was usually a military title, now used to mean prince or as a title for various rulers or chiefs.” The New Encyclopedia of Islam, By Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith, Rowman Altamira, 2003, p.48

In comparison to the western titles, by its origin and meaning, the title “Amir” would be equivalent to the title “Duke”, not “Prince”, since both “Amir” and “Duke” have a military root and meaning.

About the title “Duke”:

“The title comes from French duc, itself from the dux, ‘leader’, a term used in Latinrepublican Rome to refer to a military commander without an official rank (particularly one of Germanic or Celtic origin), and later coming to mean the leading military commander of a province.” https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke

A sovereign ruler using the title “Sheikh” or even “Hakim” is an “Emir” ‘per se‘ (intrinsically). In other words, even if the title is not openly used, it’s definitely implied. That tradition is what makes so natural for the aforementioned rulers to “update” their titles.

* More about the difference of the Arab titles, please CLICK HERE

* More about the sovereign rights of the El Chemor family according to international law, please CLICK HERE

5. The heirs of a sovereign house (observed the laws of succession) are princes regardless of the fact that they use the title or not – Examples: the archdukes of Austria, the Tsareviches and grand-dukes of the Russian empire were/are princes even thought they didn’t use the title officially.

6. To avoid the confusion – there are several categories of “sheikh” titles in Lebanon bestowed by princes after the Ottoman invasion. Those titles are “noble” not “Royal”. Differently from the El Chemor Sheikhs, the “post-Ottoman sheikhs” were not natural “sovereign or semi-sovereign” tribal leaders but wealthy notable commoners elevated to nobility.

“… [the tribal Sheikh] was a hereditary feudal chief whose authority over a particular district was vested within a patrilineal kinship group. He lived in his own village and maintained ties of patronage with his atba’ [following]. In contrast, the multazim [Sheikh] was not indigenous to the tax farm he controlled. He was more akin to a government official than a feudal sheikh.” “Lebanon’s Predicament“, Columbia, 1987, Samir Khalaf

* More about the different categories of “sheikh” titles in Lebanon, please CLICK HERE